Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe stakes have never been higher in the Ukraine-Russia war.

In the week that saw the conflict pass its 1000th day, Western powers substantially boosted Ukraine’s military arsenal – and the Kremlin made its loudest threats yet of a nuclear strike.

Here is how the last week played out – and what it means.

The West bolsters Ukraine

Late on Sunday night, reports emerged that outgoing US President Joe Biden had given Ukraine permission to use longer-range ATACMS missiles to strike targets inside Russia.

The move marked a major policy change by Washington – which for months had refused Ukraine’s requests to use the missiles beyond its own borders.

After the decision was leaked to the press, a volley of ATACMS missiles were fired by Ukraine into Russia’s Bryansk region.

The Kremlin said six were fired, with five intercepted, while anonymous US officials claimed it was eight, with two intercepted.

Whatever the specifics, this was a landmark moment: American-made missiles had struck Russian soil for the first time in this war.

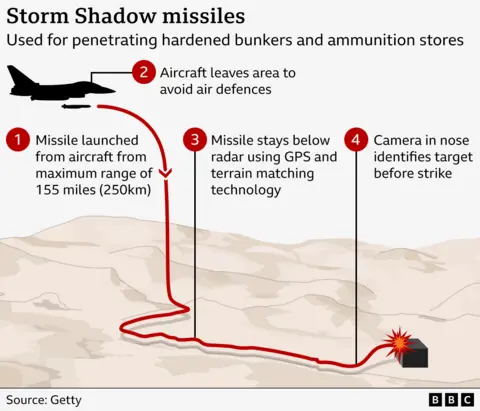

Then on Wednesday, Ukraine launched UK-supplied Storm Shadow missiles at targets in Russia’s Kursk region – where Ukrainian troops have seized a roughly 600-sq km (232 sq mile) patch of Russian territory.

Later in the week, Biden added the final element of a ramped-up weapons arsenal to Ukraine by approving the use of anti-personnel landmines.

Simple, controversial, but highly-effective, landmines are a crucial part of Ukraine’s defences on the eastern frontline – and it is hoped their use could help slow Russia’s advance.

With three swift decisions, over a few seismic days, the West signalled to the world that its support for Ukraine was not about to vanish.

Russia raises nuclear stakes

If Ukraine’s western allies raised the stakes this week – so too did Moscow.

On Tuesday, the 1000th day of the war, Putin pushed through changes to Russia’s nuclear doctrine, lowering the threshold for the use of nuclear weapons.

The doctrine now says an attack from a non-nuclear state, if backed by a nuclear power, will be treated as a joint assault on Russia.

The Kremlin then took its response a step further by deploying a new type of missile – “Oreshnik” – to strike the Ukrainian city of Dnipro.

Putin claimed it travelled at 10 times the speed of sound – and that there are “no ways of counteracting this weapon”.

Most observers agree the strike was designed to send a warning: that Russia could, if it chose, use the new missile to deliver a nuclear weapon.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSuch posturing would once have caused serious concern in the West. Now, not so much.

Since the start of the conflict nearly three years ago, Putin has repeatedly laid out nuclear “red lines’” which the West has repeatedly crossed. It seems many have become used to Russia’s nuclear “sabre-rattling”.

And why else do Western leaders feel ready to gamble with Russia’s nuclear threats? China.

Beijing has become a vital partner for Moscow in its efforts to soften the impact of sanctions imposed by the US and other countries.

China, the West believes, would react with horror at the use of nuclear weapons – thus discouraging Putin from making true on his threats.

A global conflict?

In a rare televised address on Thursday evening, the Russian president warned that the war had “acquired elements of a global character”.

That assessment was echoed by Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk, who said “the threat is serious and real when it comes to global conflict”.

The US and UK are now more deeply involved than ever – while the deployment of North Korean troops to fight alongside Russia saw another nuclear power enter the war.

North Korean leader Kim Jong Un said on Thursday that “never before” has the threat of a nuclear war been greater, blaming the US for its “aggressive and hostile” policy towards Pyongyang.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBiden out, Trump in

So, why are we seeing these developments now?

The likely reason is the impending arrival of US President-elect Donald Trump, who will officially enter the White House on 20 January.

While on the campaign trail, Trump vowed to end the war within “24 hours”.

Those around him, like Vice President-elect JD Vance, have signalled that will mean compromises for Ukraine, likely in the form of giving up territory in the Donbas and Crimea.

That goes against the apparent stance of the Biden administration – whose decisions this week point to a desire to get as much aid through the door as possible before Trump enters office.

But some are more bullish about Ukraine’s prospects with Trump in power.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUkrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said himself Kyiv would like to end the war through “diplomatic means” in 2025.

Former Ukrainian foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba told the BBC this week: “President Trump will undoubtedly be driven by one goal, to project his strength, his leadership… And show that he is capable of fixing problems which his predecessor failed to fix.”

“As much as the fall of Afghanistan inflicted a severe wound on the foreign policy reputation of the Biden administration, if the scenario you mentioned is to be entertained by President Trump, Ukraine will become his Afghanistan, with equal consequences.”

“And I don’t think this is what he’s looking for.”

This week’s developments may not be the start of the war escalating out of control – but the start of a tussle for the strongest negotiating position in potential future talks to end it.